Lady Catherine de Burgh “If you were sensible of your own good, you would not wish to quit the sphere in which you have been brought up."

Miss Elizabeth Bennet “In marrying your nephew, I should not consider myself as quitting that sphere. He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman's daughter; so far we are equal."

Lady Catherine "True. You are a gentleman's daughter. But who was your mother? Who are your uncles and aunts? Do not imagine me ignorant of their condition."

This Pride and Prejudice exchange epitomises the attitude to class in Regency England. From the beginning, children were taught to know their place in society. The catechism of the Church of England taught that it was part of their duty to their neighbour ‘to honour and obey the King, and all that are put in authority under him: To submit myself to all my governors, teachers, spiritual pastors and masters: To order myself lowly and reverently to all my betters’.

This teaching was expressed more simply and more drastically in 1848 in the hymn ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ by Mrs Cecil Alexander. The third verse, which today is frequently omitted, reads:

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

God made them high and lowly

And ordered their estate.

To wish ‘to quit the sphere in which you had been brought up’ was, accordingly, to defy God’s will.

But who, in Jane Austen’s day, was a gentleman? Barclay’s English Dictionary published in 1813, defines the ‘Gentleman’ as: ‘A person of noble birth or descended of a family which had long borne arms. Chamberlain observes that, in strictness, a gentleman is one whose ancestors have been freemen, and have owed obedience to none but the prince; on which footing no man can be a gentleman but one who is born such. But among us, the term Gentleman is applicable to all above a yeoman; so that noblemen may be properly called gentlemen.’ However, Barclay seems to contradict this last pronouncement by defining ‘Gentry’ as ‘a rank of persons between the nobility and the vulgar’ and a ‘Gentlewoman’ as ‘a woman of birth, or one superior to the vulgar, both in wealth and behaviour’.

So we have three criteria, birth, wealth and behaviour. While birth cannot be changed, wealth and behaviour may make up for a lack of it.

In A Treatise on the Wealth, Power and Resources of the British Empire, published in 1814, Patrick Colquhoun classifies Gentry as ‘Baronets, Knights and Esquires, and Gentlemen and Ladies living on [unearned] Incomes’. Colquhoun puts the average annual income of this last group at £800.

Returning to Pride and Prejudice, Mr Darcy and Mr Bennet with annual incomes from their estates of £10,000 and £2,000 respectively are both gentlemen. Although Mr Bingley’s inherited fortune of £100,000 originated in trade, his proposed purchase of an estate together with his gentleman-like behaviour will move him and his family into the landed class. Mrs Bennet’s brother, Mr Gardiner, on the other hand, ‘a man who lived by trade, and within view of his own warehouses’ and whose behaviour is eminently gentleman-like, is not a member of the gentry although his income quite likely equalled or exceeded that of his brother-in-law.

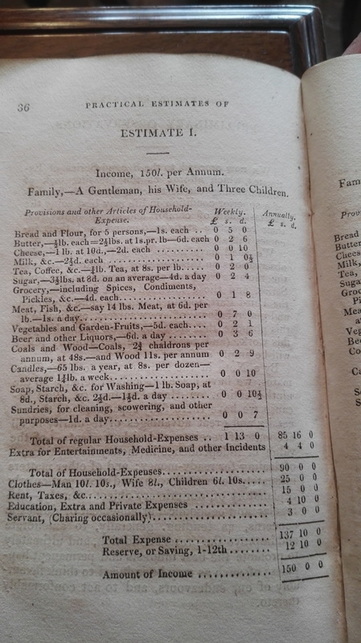

What was the minimum income necessary to be able to live as a gentleman? I recently discovered a treatise on Practical Domestic Economy published in 1823 which gives examples of 'practical estimates of household expenses' for different incomes. All are for a family of a husband, wife and three children. They are grouped into three sections:

Indeed, if we imagine Mr Bennet dead and Wickham having once more had to resign his commission, it could well be him and Lydia trying to make ends meet on £150 per year. We can only be sorry for their children, if any.

PS If you are unfamiliar with old money and would like to know more about how Pounds, Shillings and Pence worked, do scroll down to the relevant blog and if you are interested in future blogs, please check out and like my Facebook page fb.me/catherinekullmannauthor

Miss Elizabeth Bennet “In marrying your nephew, I should not consider myself as quitting that sphere. He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman's daughter; so far we are equal."

Lady Catherine "True. You are a gentleman's daughter. But who was your mother? Who are your uncles and aunts? Do not imagine me ignorant of their condition."

This Pride and Prejudice exchange epitomises the attitude to class in Regency England. From the beginning, children were taught to know their place in society. The catechism of the Church of England taught that it was part of their duty to their neighbour ‘to honour and obey the King, and all that are put in authority under him: To submit myself to all my governors, teachers, spiritual pastors and masters: To order myself lowly and reverently to all my betters’.

This teaching was expressed more simply and more drastically in 1848 in the hymn ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ by Mrs Cecil Alexander. The third verse, which today is frequently omitted, reads:

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

God made them high and lowly

And ordered their estate.

To wish ‘to quit the sphere in which you had been brought up’ was, accordingly, to defy God’s will.

But who, in Jane Austen’s day, was a gentleman? Barclay’s English Dictionary published in 1813, defines the ‘Gentleman’ as: ‘A person of noble birth or descended of a family which had long borne arms. Chamberlain observes that, in strictness, a gentleman is one whose ancestors have been freemen, and have owed obedience to none but the prince; on which footing no man can be a gentleman but one who is born such. But among us, the term Gentleman is applicable to all above a yeoman; so that noblemen may be properly called gentlemen.’ However, Barclay seems to contradict this last pronouncement by defining ‘Gentry’ as ‘a rank of persons between the nobility and the vulgar’ and a ‘Gentlewoman’ as ‘a woman of birth, or one superior to the vulgar, both in wealth and behaviour’.

So we have three criteria, birth, wealth and behaviour. While birth cannot be changed, wealth and behaviour may make up for a lack of it.

In A Treatise on the Wealth, Power and Resources of the British Empire, published in 1814, Patrick Colquhoun classifies Gentry as ‘Baronets, Knights and Esquires, and Gentlemen and Ladies living on [unearned] Incomes’. Colquhoun puts the average annual income of this last group at £800.

Returning to Pride and Prejudice, Mr Darcy and Mr Bennet with annual incomes from their estates of £10,000 and £2,000 respectively are both gentlemen. Although Mr Bingley’s inherited fortune of £100,000 originated in trade, his proposed purchase of an estate together with his gentleman-like behaviour will move him and his family into the landed class. Mrs Bennet’s brother, Mr Gardiner, on the other hand, ‘a man who lived by trade, and within view of his own warehouses’ and whose behaviour is eminently gentleman-like, is not a member of the gentry although his income quite likely equalled or exceeded that of his brother-in-law.

What was the minimum income necessary to be able to live as a gentleman? I recently discovered a treatise on Practical Domestic Economy published in 1823 which gives examples of 'practical estimates of household expenses' for different incomes. All are for a family of a husband, wife and three children. They are grouped into three sections:

- Ten estimates for families with annual incomes ranging from £62 to £125 per annum providing for articles of necessity only.

- Eight estimates for ‘families in a superior condition of life’, with annual incomes ranging from £150 to £750. As the incomes increase, we see the addition of servants, ranging from £3 per annum for ‘occasional charring’ at the lowest level to £40 per annum for ‘three maids and ‘one man as groom and footman’ at the top of the scale, and horses, ranging from ‘a horse and occasional groom @ £42 per annum for those with an annual income of £400 to ‘two horses@ £65/17s/6d plus a gig or other two-wheel carriage @ £12 for those with £750 at their disposal. The cost of their groom is included in the cost for servants.

- Seven estimates showing how ‘Gentlemen, by practical regulations, may best enjoy all the superior elegancies of life which their respective fortunes can attain.’ Incomes range from £I,000 to £5,000 per annum, the latter providing for an ‘Establishment of Thirteen Male and Nine Female servants, ten horses, a coach, a curricle and a Tilbury chaise of gig.’ And Mr Darcy’s income was twice that.

- The couples in the first group are described as ‘a man and his wife’, while those in the other groups are ‘a gentleman and his lady’.

- As a writer, I could not help wondering about the unfortunate gentleman trying to support his lady and three children on £150 per annum (below).

Indeed, if we imagine Mr Bennet dead and Wickham having once more had to resign his commission, it could well be him and Lydia trying to make ends meet on £150 per year. We can only be sorry for their children, if any.

PS If you are unfamiliar with old money and would like to know more about how Pounds, Shillings and Pence worked, do scroll down to the relevant blog and if you are interested in future blogs, please check out and like my Facebook page fb.me/catherinekullmannauthor