Free Stuff

These scenes and short stories are all copyright Catherine Kullmann and may not be copied, reproduced or disseminated in any form whatsoever without my express permission. If you would like to be kept informed of new material here, please subscribe to my newsletter on my home page Home

Summer Fair

This story was written for Helen Hollick's Advent series Diamond Tales—The Story Behind The Song

See if you can guess the song.

“I met him, you know.”

“You did what, Oma?” Anna asked incredulously.

Her grandmother smiled and paused the film. “It’s true. In 1959 at the Johanneskirmes, one of the biggest summer fairs in Hesse. People came from miles around, including lots of G.Is from the American barracks, all eager to talk to the Fräuleins.

"My friend Christa and I were both seventeen and had just finished our first year at Commercial College. Next year we would qualify as secretaries. We both had new dresses—hers was pink and mine blue—with white polka dots and white belts, collars and cuffs. We had stiffened our slips with sugar water to support the full skirts—oh, we thought we were the bee’s knees!

“The Amis were very different to the German boys we knew from school and dancing class. They were older, very smart in their dress uniforms and smelled of American cigarettes, spearmint chewing gum and the colognes and pomades they used on their close-shaven cheeks and short hair. They didn’t ask if they might accompany us, but walked beside us, with smiles and “Hi, Fräuleins”, and sort of drifted in among us girls so that before we knew it, we had split up into couples. By the time we reached the fairground, we were a group of twelve—six German girls and six Amis.

“My G.I. was called Hank; he was blonde with broad shoulders, blue eyes and a crooked smile and spoke with a sexy drawl. You could imagine him as a cowboy in a movie. He knew some German—his grandparents were from Germany—and I had worked hard at my English so we could talk together better than most of the other couples.

“As we neared the fairgrounds we could hear the oompah-pah-pah of the brass band and girls shrieking as their boys tugged hard on the ropes so that the swing-boats went right up to the bar. And then there was that fairground smell--Bratwurst, candyfloss, sizzling potato cakes, burnt almonds and sweet fried dough, all mixed with the oily smell of hot engines and the heavy scent of the linden trees that shaded one end of the grounds. Even today, when I smell it I am seventeen again.

“We strolled through the lanes between the booths, talking and laughing. We stopped to watch a puppet show—the Amis laughed as much as the children at the antics of Kasperle and his crew. Of course, they had to have a go at the shooting-stand. They didn’t do too badly, but then Ilse came up and beat them all. They couldn’t believe it. She won a teddy-bear which she insisted on presenting to her G.I., just the way a boy would give his prize to a girl. So he had to carry it the whole time.

“We tried the chair-o’-planes and the swing-boats, and then we all got into the bumper cars and whizzed around the floor, crashing into each other until we were dizzy and our throats dry from screaming. As soon as we stopped, we headed to the tables and benches near the bandstand for an apple spritzer or a beer. I felt so grown-up. It was the first time I had been allowed stay so late. Other years I had to go home once the afternoon band stopped playing.

“I was mortified when Willi got up on the stage. He wasn’t a bad singer, but so old-fashioned. The Amis seemed to like our folk songs though, and clapped and hummed along with everyone else. Willi’s last song was ‘Muss i denn, muss i denn zum Städele hinaus?

“‘What language was that?” Hank asked afterwards. ‘I couldn’t understand a word.’

“‘It’s Swabian dialect’, I told him. ‘An apprentice has passed his journeyman exams and now must leave town to work elsewhere for a year. He is saying goodbye to his sweetheart, promising to remain true to her. They’ll marry if she still loves him when he returns.’

“‘Like us,” one of the G.Is said. “Do you know it? Sing it again.’

“So we girls sang and they hummed along. The second time, they made a stab at the chorus. It was a real tongue twister for them and the people around us laughed, but not unkindly.

“Let’s try that caterpillar ride,” one of the boys said suddenly. So off we went. I was a little nervous because, well, when the hood closed over the little carriages—”

“Hank might kiss you,” her granddaughter offered. “Was it your first kiss, Oma?”

“Ja. He was nice—didn’t try to maul me or anything like that. Afterwards, he bought me a gingerbread heart on a ribbon to hang around my neck. Then the dance music started. They weren’t all used to our sort of dancing—there was no swing or rock and roll, but they soon got the hang of it. Hank was a good dancer, he held you properly, not too tight but firm enough that it was easy to follow him. It grew dark, and strings of lanterns were lit. I didn’t want the evening to end, but I had to be home by midnight and the boys had to be back at the base by then too. So, about a quarter-past-eleven, Christa and her G.I. and Hank and I took a cab to our home—it wasn’t very far but too far for them to walk us home before heading for the base. Christa’s boy started to hum ‘Muss i denn”, and we all joined in.

“They saw us to the door. There was just time for another quick kiss before my father opened it. They said ‘auf Wiedersehen’ and the night was over.”

“And that,” Anna’s grandmother said as she picked up the remote again, “is how Christa Hartmann and I taught your grandfather and Elvis Presley the melody and chorus of Wooden Heart.”

© Catherine Kullmann, 2018

This story is completely fictional, as are the characters except for Elvis himself. He was stationed in Germany between October 1958 and March 1960 during his military service. The melody and original, German chorus of Muss i denn, muss i denn zum Städele hinaus? were used for the song Wooden Heart in the 1960 film G. I. Blues.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05ZgyoZvhgI Clip from G.I. Blues

See if you can guess the song.

“I met him, you know.”

“You did what, Oma?” Anna asked incredulously.

Her grandmother smiled and paused the film. “It’s true. In 1959 at the Johanneskirmes, one of the biggest summer fairs in Hesse. People came from miles around, including lots of G.Is from the American barracks, all eager to talk to the Fräuleins.

"My friend Christa and I were both seventeen and had just finished our first year at Commercial College. Next year we would qualify as secretaries. We both had new dresses—hers was pink and mine blue—with white polka dots and white belts, collars and cuffs. We had stiffened our slips with sugar water to support the full skirts—oh, we thought we were the bee’s knees!

“The Amis were very different to the German boys we knew from school and dancing class. They were older, very smart in their dress uniforms and smelled of American cigarettes, spearmint chewing gum and the colognes and pomades they used on their close-shaven cheeks and short hair. They didn’t ask if they might accompany us, but walked beside us, with smiles and “Hi, Fräuleins”, and sort of drifted in among us girls so that before we knew it, we had split up into couples. By the time we reached the fairground, we were a group of twelve—six German girls and six Amis.

“My G.I. was called Hank; he was blonde with broad shoulders, blue eyes and a crooked smile and spoke with a sexy drawl. You could imagine him as a cowboy in a movie. He knew some German—his grandparents were from Germany—and I had worked hard at my English so we could talk together better than most of the other couples.

“As we neared the fairgrounds we could hear the oompah-pah-pah of the brass band and girls shrieking as their boys tugged hard on the ropes so that the swing-boats went right up to the bar. And then there was that fairground smell--Bratwurst, candyfloss, sizzling potato cakes, burnt almonds and sweet fried dough, all mixed with the oily smell of hot engines and the heavy scent of the linden trees that shaded one end of the grounds. Even today, when I smell it I am seventeen again.

“We strolled through the lanes between the booths, talking and laughing. We stopped to watch a puppet show—the Amis laughed as much as the children at the antics of Kasperle and his crew. Of course, they had to have a go at the shooting-stand. They didn’t do too badly, but then Ilse came up and beat them all. They couldn’t believe it. She won a teddy-bear which she insisted on presenting to her G.I., just the way a boy would give his prize to a girl. So he had to carry it the whole time.

“We tried the chair-o’-planes and the swing-boats, and then we all got into the bumper cars and whizzed around the floor, crashing into each other until we were dizzy and our throats dry from screaming. As soon as we stopped, we headed to the tables and benches near the bandstand for an apple spritzer or a beer. I felt so grown-up. It was the first time I had been allowed stay so late. Other years I had to go home once the afternoon band stopped playing.

“I was mortified when Willi got up on the stage. He wasn’t a bad singer, but so old-fashioned. The Amis seemed to like our folk songs though, and clapped and hummed along with everyone else. Willi’s last song was ‘Muss i denn, muss i denn zum Städele hinaus?

“‘What language was that?” Hank asked afterwards. ‘I couldn’t understand a word.’

“‘It’s Swabian dialect’, I told him. ‘An apprentice has passed his journeyman exams and now must leave town to work elsewhere for a year. He is saying goodbye to his sweetheart, promising to remain true to her. They’ll marry if she still loves him when he returns.’

“‘Like us,” one of the G.Is said. “Do you know it? Sing it again.’

“So we girls sang and they hummed along. The second time, they made a stab at the chorus. It was a real tongue twister for them and the people around us laughed, but not unkindly.

“Let’s try that caterpillar ride,” one of the boys said suddenly. So off we went. I was a little nervous because, well, when the hood closed over the little carriages—”

“Hank might kiss you,” her granddaughter offered. “Was it your first kiss, Oma?”

“Ja. He was nice—didn’t try to maul me or anything like that. Afterwards, he bought me a gingerbread heart on a ribbon to hang around my neck. Then the dance music started. They weren’t all used to our sort of dancing—there was no swing or rock and roll, but they soon got the hang of it. Hank was a good dancer, he held you properly, not too tight but firm enough that it was easy to follow him. It grew dark, and strings of lanterns were lit. I didn’t want the evening to end, but I had to be home by midnight and the boys had to be back at the base by then too. So, about a quarter-past-eleven, Christa and her G.I. and Hank and I took a cab to our home—it wasn’t very far but too far for them to walk us home before heading for the base. Christa’s boy started to hum ‘Muss i denn”, and we all joined in.

“They saw us to the door. There was just time for another quick kiss before my father opened it. They said ‘auf Wiedersehen’ and the night was over.”

“And that,” Anna’s grandmother said as she picked up the remote again, “is how Christa Hartmann and I taught your grandfather and Elvis Presley the melody and chorus of Wooden Heart.”

© Catherine Kullmann, 2018

This story is completely fictional, as are the characters except for Elvis himself. He was stationed in Germany between October 1958 and March 1960 during his military service. The melody and original, German chorus of Muss i denn, muss i denn zum Städele hinaus? were used for the song Wooden Heart in the 1960 film G. I. Blues.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05ZgyoZvhgI Clip from G.I. Blues

Twelfth Night at Malvin Abbey

A Perception & Illusion Intermezzo

Catherine Kullmann

!!!CONTAINS SPOILERS!!!

This episode was deleted from the original draft of Perception & Illusion. It takes place between Chapter Twenty-Eight and the Finale of P&I and, I repeat, contains massive spoilers. I strongly advise you to read Perception & Illusion first.

If you have already read P&I, and enjoy revisiting the characters and learning more about ‘what happened next’, this is for you.

Catherine Kullmann

January 2021

A Perception & Illusion Intermezzo

Catherine Kullmann

!!!CONTAINS SPOILERS!!!

This episode was deleted from the original draft of Perception & Illusion. It takes place between Chapter Twenty-Eight and the Finale of P&I and, I repeat, contains massive spoilers. I strongly advise you to read Perception & Illusion first.

If you have already read P&I, and enjoy revisiting the characters and learning more about ‘what happened next’, this is for you.

Catherine Kullmann

January 2021

Chapter One

Tamm, December 1814

“Clarissa has invited us to Malvin Abbey for Twelfth Night,” Hugo said. “What do you think, Lallie? Would it be too much for you?”

Lallie Tamrisk shook her head. “From what I understand, at six months, one is still quite comfortable. It must depend on the weather, of course, but she will know that. Do you wish to go?”

He handed her his sister’s letter. “She writes she is very anxious to welcome us to Malvin now that they have returned from Brussels, but—”

“Don’t you wish to go?”

“Yes. No. I don’t know.”

Lallie eyed her husband who had lost his usual composure at the thought of seeing his eldest sister again. “You parted in Brussels on very bad terms. I thought you had resolved your differences after she sent you that very handsome apology, but you seem still to harbour some resentment—or reservations, at least?”

He shrugged. “Sometimes I think I owe her an apology—not for what I said, but how I said it.”

“I doubt if she expects one. If you had not spoken so forcefully, she might not have been compelled to reconsider her treatment of you. But I think we should go, Hugo. It will be good for both of you to meet on more amicable terms. Besides, I should like to see them all again, and the Halworths too. It will be my last opportunity to get away from Tamm for some months.”

“Very well. We’ll go, weather and your health permitting. Clarissa will understand when I tell her you are increasing.”

She looked up from his sister’s letter. “There is to be a fancy-dress ball at Malvin. I must talk to Nancy about a costume.”

“Nancy thinks I should be able to do something with the Grecian dress,” Lallie told her husband later that day.

Hugo jerked upright from his relaxed sprawl beside the music room fire. “Clio’s dress?”

Before he could say anything more, Lallie rushed on. “The fabric is very finely pleated; there are yards and yards of it, held in place with cords. If they were not so tight, and knotted more under my breast than at my waist—oh, it might be easier to show you.”

She disappeared. leaving Hugo to gaze after her, wondering how the devil he was to extricate himself from this trap. He had bitten back an instinctive and incisive “absolutely not; I forbid it,” but still felt that the gown was anything other than proper.

With a mental appeal to the heavens for inspiration, he followed her over to their bedroom, where, Nancy in attendance, she was experimenting with different ways of catching the gown with the cords.

“You’d get away with it now, Miss Lallie,” Nancy said, “but there’s no doubt you’ll be showing more in six weeks’ time. Are you going to wear the mask as well?”

“No, nor the wig,” Lallie answered, to her husband’s relief. “They’re hot and uncomfortable. I thought we could contrive a Grecian style for my hair.”

“I can let out the seams – we could even insert a contrasting colour at the sides, and it drapes nicely at the breast. But won’t it be too cold in January? You’ll need some sort of shawl.”

Lallie turned to see the back of the gown in the mirror and noticed her husband leaning against the doorframe. “What do you think?” She revolved slowly in front of him.

She looked delectable, but to his faint regret, without the other accoutrements of Clio’s costume, the gown didn’t evoke his mysterious muse of Burlington House. “If you only wear the gown, I don’t think anyone will connect you with Clio, especially if you eschew that white paint.”

Lallie shuddered. “Dreadful stuff! It took so long to get it off the last time.”

"Nancy is right—you will need a shawl. Malvin can be draughty. Wait here–I won’t be long.” He left the room and soon returned bearing two large portfolios. “I don’t think I’ve even shown you these; I purchased them in Rome – they are depictions of antique vases and marbles.” He started to leaf through the first one. “There was one statue in particular from Herculaneum—of Athena. She’s wearing a loose over-garment. Could you contrive something of that sort? It need not be white, they used quite strong colours as well.”

Lallie scrutinised the engraving. “I like the way the tunic is cut. It reaches to the knee on the one side but only below the hip on the other. That slit on the long side would make it easy to move.”

“The pleats and upside-down vee at the waist would make it drape flatteringly over the babe,” Nancy said.

“I wonder could one adapt the idea for an overdress for every day,” Lallie said. “It would be more becoming and comfortable in the final months of a confinement than a short, tight spencer.”

“I don’t see why not, Miss Lallie,” Nancy said. “I’ll tack something together so that we can try the effect.”

Lallie shot her husband a teasing smile. “Everyone will be trying to find out the name of my new modiste. But help me out of this now, Nancy, it’s almost time to go down for dinner.”

Lallie watched appreciatively as Hugo took off his dressing-gown and got into bed beside her. “What will you wear on Twelfth Night? The dreary domino that gentlemen tend to fall back on?”.

“I suppose so. Though they are deuced uncomfortable.”

“It’s not a masquerade, but fancy dress. You could complement me and wear something from the antique world, a toga perhaps or just a tunic and cloak. We might get some ideas from your books of engravings.”

His look of horror was too much for her and she collapsed laughing against her pillows as he said firmly “I refuse even to consider any costume that requires me to bare my legs in society.”

“I have always thought them very well-shaped legs,” she murmured, turning on her side to face him and running her hand over his hip and down his thigh as she spoke.”

“Do you? Such approbation is praise indeed. Now, if you were to move your hand a little more—just there—I should feel doubly appreciated.”

“Mmm, aren’t there some portraits of your ancestors whose garments accentuate this part of the body? I seem to remember seeing a likeness of Henry VIII as well that emphasized his—manliness. Do you mean you would prefer such a costume?”

“Wear a codpiece? You little minx!”

She measured him with her hand. “It would have to be very large, of course.”

“I see I shall have to stop thy mouth,” he groaned and rolled over to kiss her deeply while at the same time settling himself between her legs. She raised her knees and clasped him with her thighs while her arms held him close.

Now they moved together to the oldest of rhythms. Not two but one, Lallie thought, as a wave carried her upwards towards a starburst of sensation that held her suspended for long moments before disintegrating into a shower of sparks. Like fireworks over the sea, she thought languidly, smiling as she met her husband’s eyes and raised her hand to brush his hair back from his forehead. He bent his head to kiss her tenderly before gently lifting himself from her to lie by her side and pillow his head on her breast.

Tamm, December 1814

“Clarissa has invited us to Malvin Abbey for Twelfth Night,” Hugo said. “What do you think, Lallie? Would it be too much for you?”

Lallie Tamrisk shook her head. “From what I understand, at six months, one is still quite comfortable. It must depend on the weather, of course, but she will know that. Do you wish to go?”

He handed her his sister’s letter. “She writes she is very anxious to welcome us to Malvin now that they have returned from Brussels, but—”

“Don’t you wish to go?”

“Yes. No. I don’t know.”

Lallie eyed her husband who had lost his usual composure at the thought of seeing his eldest sister again. “You parted in Brussels on very bad terms. I thought you had resolved your differences after she sent you that very handsome apology, but you seem still to harbour some resentment—or reservations, at least?”

He shrugged. “Sometimes I think I owe her an apology—not for what I said, but how I said it.”

“I doubt if she expects one. If you had not spoken so forcefully, she might not have been compelled to reconsider her treatment of you. But I think we should go, Hugo. It will be good for both of you to meet on more amicable terms. Besides, I should like to see them all again, and the Halworths too. It will be my last opportunity to get away from Tamm for some months.”

“Very well. We’ll go, weather and your health permitting. Clarissa will understand when I tell her you are increasing.”

She looked up from his sister’s letter. “There is to be a fancy-dress ball at Malvin. I must talk to Nancy about a costume.”

“Nancy thinks I should be able to do something with the Grecian dress,” Lallie told her husband later that day.

Hugo jerked upright from his relaxed sprawl beside the music room fire. “Clio’s dress?”

Before he could say anything more, Lallie rushed on. “The fabric is very finely pleated; there are yards and yards of it, held in place with cords. If they were not so tight, and knotted more under my breast than at my waist—oh, it might be easier to show you.”

She disappeared. leaving Hugo to gaze after her, wondering how the devil he was to extricate himself from this trap. He had bitten back an instinctive and incisive “absolutely not; I forbid it,” but still felt that the gown was anything other than proper.

With a mental appeal to the heavens for inspiration, he followed her over to their bedroom, where, Nancy in attendance, she was experimenting with different ways of catching the gown with the cords.

“You’d get away with it now, Miss Lallie,” Nancy said, “but there’s no doubt you’ll be showing more in six weeks’ time. Are you going to wear the mask as well?”

“No, nor the wig,” Lallie answered, to her husband’s relief. “They’re hot and uncomfortable. I thought we could contrive a Grecian style for my hair.”

“I can let out the seams – we could even insert a contrasting colour at the sides, and it drapes nicely at the breast. But won’t it be too cold in January? You’ll need some sort of shawl.”

Lallie turned to see the back of the gown in the mirror and noticed her husband leaning against the doorframe. “What do you think?” She revolved slowly in front of him.

She looked delectable, but to his faint regret, without the other accoutrements of Clio’s costume, the gown didn’t evoke his mysterious muse of Burlington House. “If you only wear the gown, I don’t think anyone will connect you with Clio, especially if you eschew that white paint.”

Lallie shuddered. “Dreadful stuff! It took so long to get it off the last time.”

"Nancy is right—you will need a shawl. Malvin can be draughty. Wait here–I won’t be long.” He left the room and soon returned bearing two large portfolios. “I don’t think I’ve even shown you these; I purchased them in Rome – they are depictions of antique vases and marbles.” He started to leaf through the first one. “There was one statue in particular from Herculaneum—of Athena. She’s wearing a loose over-garment. Could you contrive something of that sort? It need not be white, they used quite strong colours as well.”

Lallie scrutinised the engraving. “I like the way the tunic is cut. It reaches to the knee on the one side but only below the hip on the other. That slit on the long side would make it easy to move.”

“The pleats and upside-down vee at the waist would make it drape flatteringly over the babe,” Nancy said.

“I wonder could one adapt the idea for an overdress for every day,” Lallie said. “It would be more becoming and comfortable in the final months of a confinement than a short, tight spencer.”

“I don’t see why not, Miss Lallie,” Nancy said. “I’ll tack something together so that we can try the effect.”

Lallie shot her husband a teasing smile. “Everyone will be trying to find out the name of my new modiste. But help me out of this now, Nancy, it’s almost time to go down for dinner.”

Lallie watched appreciatively as Hugo took off his dressing-gown and got into bed beside her. “What will you wear on Twelfth Night? The dreary domino that gentlemen tend to fall back on?”.

“I suppose so. Though they are deuced uncomfortable.”

“It’s not a masquerade, but fancy dress. You could complement me and wear something from the antique world, a toga perhaps or just a tunic and cloak. We might get some ideas from your books of engravings.”

His look of horror was too much for her and she collapsed laughing against her pillows as he said firmly “I refuse even to consider any costume that requires me to bare my legs in society.”

“I have always thought them very well-shaped legs,” she murmured, turning on her side to face him and running her hand over his hip and down his thigh as she spoke.”

“Do you? Such approbation is praise indeed. Now, if you were to move your hand a little more—just there—I should feel doubly appreciated.”

“Mmm, aren’t there some portraits of your ancestors whose garments accentuate this part of the body? I seem to remember seeing a likeness of Henry VIII as well that emphasized his—manliness. Do you mean you would prefer such a costume?”

“Wear a codpiece? You little minx!”

She measured him with her hand. “It would have to be very large, of course.”

“I see I shall have to stop thy mouth,” he groaned and rolled over to kiss her deeply while at the same time settling himself between her legs. She raised her knees and clasped him with her thighs while her arms held him close.

Now they moved together to the oldest of rhythms. Not two but one, Lallie thought, as a wave carried her upwards towards a starburst of sensation that held her suspended for long moments before disintegrating into a shower of sparks. Like fireworks over the sea, she thought languidly, smiling as she met her husband’s eyes and raised her hand to brush his hair back from his forehead. He bent his head to kiss her tenderly before gently lifting himself from her to lie by her side and pillow his head on her breast.

Chapter Two

Malvin Abbey, January 1815

Clarissa must have given instructions that she be alerted as soon as their carriages were in sight, for she came down the steps just as the travelling chariot drew up at Malvin Abbey. Hugo alighted, astonished by this public, almost formal welcome. On his previous, infrequent visits, he had been received by the butler who had then announced his arrival to his master or mistress if either had been there to receive him.

He helped Lallie step down before turning to greet his sister, a sarcastic comment on this unprecedented honour honed and hovering on the tip of his tongue. She appeared unusually nervous and his brother-in-law who stood almost protectively beside her was looking from her to him in concern.

Clarissa held out her hand and swallowed visibly. “Welcome, brother,” she said, with a tentative smile.

Lallie glanced at him, her quick minatory frown and slight shake of the head cautioning him against, against what? Pokering up, he thought. He had accepted his sister’s comprehensive apology for past slights, yet here he was about to revert to the old habits that must be cast off if they were to build a new, more affectionate relationship. Clarissa had led the way and his instinctive response had been to disparage her gesture. Ashamed, he opened his arms to her.

“Clarissa.”

She hesitated for a moment and then came into them; he felt more than heard her choked sob and her arms came around him in a warm embrace.

“Oh, Hugo.” Her voice wobbled.

“Ssh. It’s all right, now, Clarrie.”

“You’re very generous,” she said reaching up to kiss him.

“No more than you,” he said gently and hugged her again before releasing her to shake hands with Tony Malvin.

“My dear Lallie, I’m so sorry to keep you standing in the cold.” Clarissa embraced her sister-in-law. “Do come in. It’s your first real visit to Malvin, isn’t it?”

“Apart from your soirée last year, - no, now it’s the year before last,” Lallie agreed with a smile.

“When you and Hugo met? I shall have to set up as a matchmaker, although indeed I am having so little success with my own children that you would be my only recommendation.

“Arthur and Matthew are young yet,” Hugo said indulgently.

“Matthew, perhaps, at twenty-three, but Arthur will be twenty-eight this year. And Arabella has had two seasons.”

“She doesn’t want for admirers,” Lord Malvin said. “For my part, I’m delighted to have my daughter at home a while longer.”

We’re just a family party tonight,” Clarissa said as she escorted Hugo and Lallie to their rooms. “Julian and Mattie are here, of course, and Henrietta and Amabel arrived earlier. All have brought their families. The other guests come tomorrow and we must be more formal, but tonight the children may come down to the large parlour for an hour before dinner.”

As they left their room later to seek out the large parlour, Lallie could not but smile at the memory of how she had found her ladyship so daunting at that previous soirée. Hugo quirked an eyebrow but was distracted by Henrietta and Charles Forbes who joined them at the head of the stairs in a flurry of exclamations and embraces.

Clarissa as materfamilias was a different person to the Viscountess Malvin, Lallie quickly discovered. The stately matron was transformed into an indulgent mother, grandmother and aunt, who did not complain when interrupted to admire a new doll, but caught the proud owner in a loving arm, saying seriously, “Just let us finish this game of spillikins, my love and then you may tell me all about Dolly. She is very pretty.”

Lallie at first experienced some difficulty in sorting out the numerous children who blithely addressed her as Aunt Lallie, especially as she was soon surrounded by the younger girls while she demonstrated an intricate form of cat’s cradle. Two of her pupils were called away to perform a song they had been practising for the occasion just before they could master the tricky transfer from one pair of hands to another, but not without extracting a promise that she would come up to the school-room the next day to resume her lessons.

Lord Malvin benevolently applauded the pretty rendition of Early One Morning, but not without muttering to Lallie “I can’t for the life of me understand why even children must bewail deceived maidens. You will have something more cheerful for us, will you not, my dear?”

She smiled at him. “Why, yes, my Lord, Hugo and I have discovered a song that is much more to your taste—the deserted maiden finds another swain and decides ‘to put off her dying to toy and to play’.”

“That’s much more the thing,” he said approvingly. “But what’s this ‘my Lord? Call me Tony—we’re all family here. I hope I may be permitted to say Lallie?”

“Of course,” Lallie agreed, wondering if she would ever find the courage to address him as he wished, for he was almost forty years older than she, and a peer besides.

“I’m very grateful to you, dear Lallie,” he said seriously, “I had never thought to see such a rapprochement between Clarissa and her brother.”

“I had very little to do with it, and if so, inadvertently. Indeed, I think it was your wife’s courage and honesty in writing to him as she did that brought about the change. One would have had to have a heart of stone to resist such an appeal.”

“She was horrified when she realised what she had done. I am convinced however that it was Hugo’s love for you that brought him to a stage where he could break the silence of years. Both Arthur and Clarissa told me how distraught he was when he discovered you gone. But I see you two have put things to rights between you.”

Lallie looked at him in surprise, flushing slightly at this reminder of her precipitate flight from Brussels. It seemed so long ago, not only in time but also when she considered the growing bond that now linked her and her husband and made it difficult to remember the arid months of their early marriage.

“You will think me an interfering old woman,” he said ruefully, “but Hugo is more like a son or nephew to me than a brother-in-law and I am pleased to see him happy. I always regretted that I could not do more for him, but Clarissa was so sorely wounded by her father and her defences are very strong. And of course, initially Hugo followed Tamm’s example in his disdain for females—well, it was to be expected I suppose and one should not blame him, but she could never see that. Once he was old enough, I had a word with him, explained that it was not at all the way a gentleman behaves. He made a handsome apology for his cutting remark, but the damage was done and he could never retrieve his position. And to be fair, she never let up either.”

“Now that their wounds have been lanced, I think their relationship must improve,” Lallie said. “Only look how well they are getting on together now. And he was very affected by the way she came out to welcome us. Previously, he said, he might not have seen either of you until dinner on the day he arrived.”

Malvin looked taken aback at this, but the clock then struck the half-hour and his wife clapped her hands.

“Time for everyone who is not yet sixteen to return upstairs,” she said “except for Roderick. Roderick, you may dine with us tonight, for you will be sixteen next month.”

Lallie was amused to note that the boy seemed equally gratified and appalled by this pronouncement.

Once the children had departed, the adults split naturally into two groups, the gentlemen gravitating towards the decanters set on a table near the window while the ladies sank into the sofas and chairs near the fire. Noticing Roderick hovering uneasily near the men as though unconvinced of his entitlement to join them, Hugo, who remembered how awkward he had felt on similar occasions in his youth, turned slightly so as to open the circle to include him.

“Did you bring the dogs, Hugo?” Arthur, who had managed to get a couple of weeks’ furlough, enquired as they discussed the possibility of taking the guns out the following day.

“Just Virgil. Horace is getting too old and Mam’selle ‘Ubertine is not fully trained. Besides she has taken a liking to my father and frequently keeps him company.”

“Mam’selle? Oh, the bitch you acquired in the Ardennes in September—an intriguing little thing.”

“With a damn good nose for following a scent. I was thinking of breeding her, but the St. John’s may be too big for her.”

“You could try a spaniel or a setter,” Roderick volunteered. “We have a new litter of setters, don’t we Papa?”

“They’re just ready to leave the mother,” Malvin agreed and cocked an eyebrow at his brother-in-law. “Interested?”

“I’ll take a look at them tomorrow,” Hugo answered. “If it should prove successful, I’ll send one of the pups back in due course, a bitch if possible.”

“Dinner is served, my Lady.”

“We won’t stand on ceremony tonight,” Clarissa declared, “as long as you gentlemen don’t insist on congregating at one end of the table. You will have time for that afterwards.” She took her husband’s arm. “For once, you may take me in, Tony, and Millicent will take my place. The rest of you may do as you please; we have too many gentlemen in any case.”

Laughing, they sorted themselves into couples; Hugo offering his arm to his sister Amabel while Arthur squired Lallie. She found herself sitting between him and Roderick, with Hugo opposite her.

“It’s the first time we have all been together since your wedding, Hugo,” Amabel stated once the polite bustle of serving one’s neighbours and oneself had died down. “How long ago that seems. I’m sure you feel it particularly, Lallie, for it is such a big change for a girl; those first months of marriage, I mean.”

“What of Hugo?” Matthew asked slyly. “He positively exudes uxoriousness.”

“What a well-turned phrase,” his eldest brother commented mockingly. “We’ll see if you can repeat it as fluently after a few glasses of Papa’s port.”

“While I deplore the verb, I readily admit to the noun.” Hugo raised his glass in silent salute to his wife, who slanted her cat’s eyes at him in return, a secret smile flirting on her lips.

At the head of the table, Lord Malvin signalled to the butler to fill up the glasses. “Let us drink to Hugo and Lallie, for it is the first time they have dined here since their marriage, and to a strong and enduring amity between our two families.”

There was very little left of St Anthony’s Abbey at Malvin save the cloisters which had long since been incorporated into a serene walled garden and it was here that Clarissa took Lallie the next morning for a quiet stroll.

“Anthony’s mother had this new wing built so that she could walk in almost all weathers, she explained as she led her sister-in-law through the long orangery. “A pretty colonnade links it with the garden and a door leads directly into the cloisters. They provide shelter in winter and shade in summer. The ballroom is above us and that staircase at the end links the two.”

“That must keep the chaperons occupied,” Lallie remarked.

“One would think so, but in fact so many people stroll through the orangery that it remains quite proper. We don’t have a proper circuit of rooms, so it is the only way to leave the ballroom without retracing one’s steps.” As she spoke Clarissa opened a wooden door set in an old stone wall and gestured to Lallie to precede her.

Stepping through, Lallie paused to admire the covered walk enclosed in grey stone; the roof was vaulted and open arcades in the inner wall led the eye to a large, square lawn that was sprinkled with snow-drops. A fountain in the centre was surrounded by neatly trimmed rose bushes with more roses growing at the four corners of the lawn. “How lovely. And it must be really beautiful when the roses are in bloom.”

“It is. The snowdrops will be followed by daffodils and then come the roses.” Clarissa pointed towards a door on the opposite side. “Through there is a bigger garden, with trees and shrubs as well as flower beds, but we thought to keep here simple.”

“It is so peaceful,” Lallie said as they slowly paced along the flagstones, stopping every so often to admire the intricately carved capitals and columns.

“You must come here whenever you wish. If I had realised you were expecting, I should never have sent an invitation, but I am so glad you came. Pray do not tire yourself, my dear; I shall quite understand if you wish to withdraw at any time.”

“Thank you. I feel very well at the moment; much better than I did in the first months.”

“That is often the case, but I remember how fatiguing I found such house-parties when I was increasing. And another twenty guests arrive today and tomorrow.”

They embarked on a second perambulation of the cloisters. “It’s wonderful to see Hugo so well and so happy,” Clarissa confided, “but I must confess, Lallie, that it only increases my guilt at my previous treatment of him. I feel quite wretched at times. And I owe you an apology, too, for my behaviour must have contributed to the estrangement between you.”

“That’s all behind us now,” Lallie said firmly, “and indeed, Clarissa, if we are to be frank, I have to tell you that I quite understand how your father’s treatment of your mother and you three sisters could have tainted your perception of your brother. At times Tamm is inclined to ramble, as if he is reliving the past, and some of his comments—I must bite my tongue so as not to respond. Sadly, he cannot change what was. Neither can you. But you had the courage to try and change what is and what will be. I can’t tell you how much I admired you for writing that letter to Hugo. It can’t have been easy for you.”

Clarissa shook her head. “I was so dismayed by my behaviour that writing the letter was a relief. I suppose the old nuns would have said I felt better for owning my fault. Do you know, Lallie, it was as if I had laid down a burden. Dear Tony encouraged me—he said my behaviour showed that I was still subject to my father’s influence and I would be much happier if I could only shake it off. He was right. I feel liberated somehow and so much lighter, especially since I received Hugo’s reply.”

“I’m so glad,” Lallie answered simply. “It helped Hugo very much, you know. You showed him, showed us that it was possible to change.”

The two women walked on in silence. “Who are your other guests?” Lallie asked curiously after some time. “You mentioned you were expecting some twenty more.”

“The most important are the Bentons. Matthew and Marfield were at school together and Lady Anna and Arabella became friendly during their come-out year, so the two families see quite a lot of one another.

“Are the Earl and Countess coming too?”

“Yes. Do you mind? Henrietta said you and she had got on very well.”

“She was very kind. I just hope that she no longer makes such a fuss about how I was ‘found—as if I had been abandoned on the church steps! After all, it was they—the Martyns, I mean, who cast off Grandmama, not the other way around.”

Clarissa gasped. “I never thought; Mr and Mrs Grey are staying with the Halworths again and I invited them all for Twelfth Night. Would that create any difficulties?”

“Not at all. I would have called on the Halworths anyway, and I shall be delighted to see my brother and sisters again.”

Malvin Abbey, January 1815

Clarissa must have given instructions that she be alerted as soon as their carriages were in sight, for she came down the steps just as the travelling chariot drew up at Malvin Abbey. Hugo alighted, astonished by this public, almost formal welcome. On his previous, infrequent visits, he had been received by the butler who had then announced his arrival to his master or mistress if either had been there to receive him.

He helped Lallie step down before turning to greet his sister, a sarcastic comment on this unprecedented honour honed and hovering on the tip of his tongue. She appeared unusually nervous and his brother-in-law who stood almost protectively beside her was looking from her to him in concern.

Clarissa held out her hand and swallowed visibly. “Welcome, brother,” she said, with a tentative smile.

Lallie glanced at him, her quick minatory frown and slight shake of the head cautioning him against, against what? Pokering up, he thought. He had accepted his sister’s comprehensive apology for past slights, yet here he was about to revert to the old habits that must be cast off if they were to build a new, more affectionate relationship. Clarissa had led the way and his instinctive response had been to disparage her gesture. Ashamed, he opened his arms to her.

“Clarissa.”

She hesitated for a moment and then came into them; he felt more than heard her choked sob and her arms came around him in a warm embrace.

“Oh, Hugo.” Her voice wobbled.

“Ssh. It’s all right, now, Clarrie.”

“You’re very generous,” she said reaching up to kiss him.

“No more than you,” he said gently and hugged her again before releasing her to shake hands with Tony Malvin.

“My dear Lallie, I’m so sorry to keep you standing in the cold.” Clarissa embraced her sister-in-law. “Do come in. It’s your first real visit to Malvin, isn’t it?”

“Apart from your soirée last year, - no, now it’s the year before last,” Lallie agreed with a smile.

“When you and Hugo met? I shall have to set up as a matchmaker, although indeed I am having so little success with my own children that you would be my only recommendation.

“Arthur and Matthew are young yet,” Hugo said indulgently.

“Matthew, perhaps, at twenty-three, but Arthur will be twenty-eight this year. And Arabella has had two seasons.”

“She doesn’t want for admirers,” Lord Malvin said. “For my part, I’m delighted to have my daughter at home a while longer.”

We’re just a family party tonight,” Clarissa said as she escorted Hugo and Lallie to their rooms. “Julian and Mattie are here, of course, and Henrietta and Amabel arrived earlier. All have brought their families. The other guests come tomorrow and we must be more formal, but tonight the children may come down to the large parlour for an hour before dinner.”

As they left their room later to seek out the large parlour, Lallie could not but smile at the memory of how she had found her ladyship so daunting at that previous soirée. Hugo quirked an eyebrow but was distracted by Henrietta and Charles Forbes who joined them at the head of the stairs in a flurry of exclamations and embraces.

Clarissa as materfamilias was a different person to the Viscountess Malvin, Lallie quickly discovered. The stately matron was transformed into an indulgent mother, grandmother and aunt, who did not complain when interrupted to admire a new doll, but caught the proud owner in a loving arm, saying seriously, “Just let us finish this game of spillikins, my love and then you may tell me all about Dolly. She is very pretty.”

Lallie at first experienced some difficulty in sorting out the numerous children who blithely addressed her as Aunt Lallie, especially as she was soon surrounded by the younger girls while she demonstrated an intricate form of cat’s cradle. Two of her pupils were called away to perform a song they had been practising for the occasion just before they could master the tricky transfer from one pair of hands to another, but not without extracting a promise that she would come up to the school-room the next day to resume her lessons.

Lord Malvin benevolently applauded the pretty rendition of Early One Morning, but not without muttering to Lallie “I can’t for the life of me understand why even children must bewail deceived maidens. You will have something more cheerful for us, will you not, my dear?”

She smiled at him. “Why, yes, my Lord, Hugo and I have discovered a song that is much more to your taste—the deserted maiden finds another swain and decides ‘to put off her dying to toy and to play’.”

“That’s much more the thing,” he said approvingly. “But what’s this ‘my Lord? Call me Tony—we’re all family here. I hope I may be permitted to say Lallie?”

“Of course,” Lallie agreed, wondering if she would ever find the courage to address him as he wished, for he was almost forty years older than she, and a peer besides.

“I’m very grateful to you, dear Lallie,” he said seriously, “I had never thought to see such a rapprochement between Clarissa and her brother.”

“I had very little to do with it, and if so, inadvertently. Indeed, I think it was your wife’s courage and honesty in writing to him as she did that brought about the change. One would have had to have a heart of stone to resist such an appeal.”

“She was horrified when she realised what she had done. I am convinced however that it was Hugo’s love for you that brought him to a stage where he could break the silence of years. Both Arthur and Clarissa told me how distraught he was when he discovered you gone. But I see you two have put things to rights between you.”

Lallie looked at him in surprise, flushing slightly at this reminder of her precipitate flight from Brussels. It seemed so long ago, not only in time but also when she considered the growing bond that now linked her and her husband and made it difficult to remember the arid months of their early marriage.

“You will think me an interfering old woman,” he said ruefully, “but Hugo is more like a son or nephew to me than a brother-in-law and I am pleased to see him happy. I always regretted that I could not do more for him, but Clarissa was so sorely wounded by her father and her defences are very strong. And of course, initially Hugo followed Tamm’s example in his disdain for females—well, it was to be expected I suppose and one should not blame him, but she could never see that. Once he was old enough, I had a word with him, explained that it was not at all the way a gentleman behaves. He made a handsome apology for his cutting remark, but the damage was done and he could never retrieve his position. And to be fair, she never let up either.”

“Now that their wounds have been lanced, I think their relationship must improve,” Lallie said. “Only look how well they are getting on together now. And he was very affected by the way she came out to welcome us. Previously, he said, he might not have seen either of you until dinner on the day he arrived.”

Malvin looked taken aback at this, but the clock then struck the half-hour and his wife clapped her hands.

“Time for everyone who is not yet sixteen to return upstairs,” she said “except for Roderick. Roderick, you may dine with us tonight, for you will be sixteen next month.”

Lallie was amused to note that the boy seemed equally gratified and appalled by this pronouncement.

Once the children had departed, the adults split naturally into two groups, the gentlemen gravitating towards the decanters set on a table near the window while the ladies sank into the sofas and chairs near the fire. Noticing Roderick hovering uneasily near the men as though unconvinced of his entitlement to join them, Hugo, who remembered how awkward he had felt on similar occasions in his youth, turned slightly so as to open the circle to include him.

“Did you bring the dogs, Hugo?” Arthur, who had managed to get a couple of weeks’ furlough, enquired as they discussed the possibility of taking the guns out the following day.

“Just Virgil. Horace is getting too old and Mam’selle ‘Ubertine is not fully trained. Besides she has taken a liking to my father and frequently keeps him company.”

“Mam’selle? Oh, the bitch you acquired in the Ardennes in September—an intriguing little thing.”

“With a damn good nose for following a scent. I was thinking of breeding her, but the St. John’s may be too big for her.”

“You could try a spaniel or a setter,” Roderick volunteered. “We have a new litter of setters, don’t we Papa?”

“They’re just ready to leave the mother,” Malvin agreed and cocked an eyebrow at his brother-in-law. “Interested?”

“I’ll take a look at them tomorrow,” Hugo answered. “If it should prove successful, I’ll send one of the pups back in due course, a bitch if possible.”

“Dinner is served, my Lady.”

“We won’t stand on ceremony tonight,” Clarissa declared, “as long as you gentlemen don’t insist on congregating at one end of the table. You will have time for that afterwards.” She took her husband’s arm. “For once, you may take me in, Tony, and Millicent will take my place. The rest of you may do as you please; we have too many gentlemen in any case.”

Laughing, they sorted themselves into couples; Hugo offering his arm to his sister Amabel while Arthur squired Lallie. She found herself sitting between him and Roderick, with Hugo opposite her.

“It’s the first time we have all been together since your wedding, Hugo,” Amabel stated once the polite bustle of serving one’s neighbours and oneself had died down. “How long ago that seems. I’m sure you feel it particularly, Lallie, for it is such a big change for a girl; those first months of marriage, I mean.”

“What of Hugo?” Matthew asked slyly. “He positively exudes uxoriousness.”

“What a well-turned phrase,” his eldest brother commented mockingly. “We’ll see if you can repeat it as fluently after a few glasses of Papa’s port.”

“While I deplore the verb, I readily admit to the noun.” Hugo raised his glass in silent salute to his wife, who slanted her cat’s eyes at him in return, a secret smile flirting on her lips.

At the head of the table, Lord Malvin signalled to the butler to fill up the glasses. “Let us drink to Hugo and Lallie, for it is the first time they have dined here since their marriage, and to a strong and enduring amity between our two families.”

There was very little left of St Anthony’s Abbey at Malvin save the cloisters which had long since been incorporated into a serene walled garden and it was here that Clarissa took Lallie the next morning for a quiet stroll.

“Anthony’s mother had this new wing built so that she could walk in almost all weathers, she explained as she led her sister-in-law through the long orangery. “A pretty colonnade links it with the garden and a door leads directly into the cloisters. They provide shelter in winter and shade in summer. The ballroom is above us and that staircase at the end links the two.”

“That must keep the chaperons occupied,” Lallie remarked.

“One would think so, but in fact so many people stroll through the orangery that it remains quite proper. We don’t have a proper circuit of rooms, so it is the only way to leave the ballroom without retracing one’s steps.” As she spoke Clarissa opened a wooden door set in an old stone wall and gestured to Lallie to precede her.

Stepping through, Lallie paused to admire the covered walk enclosed in grey stone; the roof was vaulted and open arcades in the inner wall led the eye to a large, square lawn that was sprinkled with snow-drops. A fountain in the centre was surrounded by neatly trimmed rose bushes with more roses growing at the four corners of the lawn. “How lovely. And it must be really beautiful when the roses are in bloom.”

“It is. The snowdrops will be followed by daffodils and then come the roses.” Clarissa pointed towards a door on the opposite side. “Through there is a bigger garden, with trees and shrubs as well as flower beds, but we thought to keep here simple.”

“It is so peaceful,” Lallie said as they slowly paced along the flagstones, stopping every so often to admire the intricately carved capitals and columns.

“You must come here whenever you wish. If I had realised you were expecting, I should never have sent an invitation, but I am so glad you came. Pray do not tire yourself, my dear; I shall quite understand if you wish to withdraw at any time.”

“Thank you. I feel very well at the moment; much better than I did in the first months.”

“That is often the case, but I remember how fatiguing I found such house-parties when I was increasing. And another twenty guests arrive today and tomorrow.”

They embarked on a second perambulation of the cloisters. “It’s wonderful to see Hugo so well and so happy,” Clarissa confided, “but I must confess, Lallie, that it only increases my guilt at my previous treatment of him. I feel quite wretched at times. And I owe you an apology, too, for my behaviour must have contributed to the estrangement between you.”

“That’s all behind us now,” Lallie said firmly, “and indeed, Clarissa, if we are to be frank, I have to tell you that I quite understand how your father’s treatment of your mother and you three sisters could have tainted your perception of your brother. At times Tamm is inclined to ramble, as if he is reliving the past, and some of his comments—I must bite my tongue so as not to respond. Sadly, he cannot change what was. Neither can you. But you had the courage to try and change what is and what will be. I can’t tell you how much I admired you for writing that letter to Hugo. It can’t have been easy for you.”

Clarissa shook her head. “I was so dismayed by my behaviour that writing the letter was a relief. I suppose the old nuns would have said I felt better for owning my fault. Do you know, Lallie, it was as if I had laid down a burden. Dear Tony encouraged me—he said my behaviour showed that I was still subject to my father’s influence and I would be much happier if I could only shake it off. He was right. I feel liberated somehow and so much lighter, especially since I received Hugo’s reply.”

“I’m so glad,” Lallie answered simply. “It helped Hugo very much, you know. You showed him, showed us that it was possible to change.”

The two women walked on in silence. “Who are your other guests?” Lallie asked curiously after some time. “You mentioned you were expecting some twenty more.”

“The most important are the Bentons. Matthew and Marfield were at school together and Lady Anna and Arabella became friendly during their come-out year, so the two families see quite a lot of one another.

“Are the Earl and Countess coming too?”

“Yes. Do you mind? Henrietta said you and she had got on very well.”

“She was very kind. I just hope that she no longer makes such a fuss about how I was ‘found—as if I had been abandoned on the church steps! After all, it was they—the Martyns, I mean, who cast off Grandmama, not the other way around.”

Clarissa gasped. “I never thought; Mr and Mrs Grey are staying with the Halworths again and I invited them all for Twelfth Night. Would that create any difficulties?”

“Not at all. I would have called on the Halworths anyway, and I shall be delighted to see my brother and sisters again.”

Chapter Three

Lallie caught sight of her husband in the long mirror and turned to inspect him. Following animated discussions that were punctuated by his refusal to wear skirts (as he described any form of robe, gown or tunic) or wigs (which effectively ruled out the preceding two centuries, as he also declined to appear as a round-head), they had settled on Elizabethan doublet and hose which, as she had acerbically pointed out, would be no more revealing than today’s silk knee-breeches or clinging pantaloons.

He cut a very dashing figure in dark burgundy that had been slashed to reveal the gold lining which was pulled through in puffs. The cut of the doublet emphasized his broad shoulders and harrow waist, while a puffed trunkhose served to spare his blushes. His netherhose were also burgundy, but with elaborate gold clocks. A white ruff set off his dark, aquiline features and a short cloak, again lined with gold, hung from his shoulders. Heeled burgundy shoes with gold buckles gave him additional height so that when Lallie stood, she found herself looking up more than usual to meet his eyes.

“You look truly splendid, Hugo. It’s fortunate that we are at your sister’s and not a more public assembly, for you would be besieged by all the females.”

He made an elaborate leg. “My eyes would only be for you, Clio. I had forgotten how delectable you looked in that gown.” He traced the neckline with a caressing finger. “It is even more enticing now. “He bent to kiss her and inhaled deeply. “I remember that perfume.”

“It’s called Les Fleurs du Parnasse’ Do you like it?”

“It’s intoxicating, Clio” he muttered, going on one knee to nibble a line of kisses from her throat to between her breasts.

“Behave, sir, or I’ll never be ready,” she protested, but softened her rebuke by holding him to her for a moment and gently ruffling his hair. He raised his head and captured her in one arm a more satisfying embrace before presenting her with a flat leather box. Lallie opened it to reveal a half-wreath of leaves and flowers cunningly fashioned in beaten gold.

“I asked Henrietta to find something appropriately classical for you to wear tonight,” Hugo explained as she stared at it, spellbound. “I didn’t think I would find the right thing in Exeter.”

“Hugo, this is ravishing. Thank you so much! You spoil me.”

“That is my privilege.”

She twined her arms around his neck to kiss him sweetly. “Thank you,” she said again, “it’s so beautiful and how clever of you to think of it. You must be reconciled with naughty Clio if you purchase her such treasures,” she added with a provocative smile.

“Very reconciled,” he murmured against her mouth. “I think you must wear that gown some evening we’re dining in our apartments.”

Lallie glanced at the clock, “It’s almost time to go down. I must ring for Nancy to help me. She will have to redo my hair without the bandeaux. This will be much prettier.”

“We’ll put on the tunic first, Miss Lallie,” Nancy said, very carefully setting down the wreath. “This is so delicate; only see how each leaf and petal is barely attached so that it seems they might be carried away by the slightest breeze. I’m afraid we’ll damage it if it catches on something as we put it over your head.”

The tunic was a soft pink, made of finely pleated linen that was cleverly cut to skim the swell of Lallie’s abdomen, its asymmetric line cunningly leading the eye away from the evidence of her pregnancy. Instead of sleeves, dropped shoulders, loosely gathered at the seam, covered her upper arms. All the edges were trimmed with entwined green and gold braid, the slight weight of which held the pleats in place.

“You won’t have the matching green in your hair now,” Nancy remarked as she removed the bandeaux and artfully settled the wreath in her mistress’s newly-styled hair

“We still have my grand-mother’s ear-rings.”

Hugo, lounging on the sofa as he watched his wife put the finishing touches to her toilette, caught his breath when she rose from the stool and turned to face him. The sparkle of her green eyes matched that of the peridots suspended from her delicate ear-lobes. The leaves and flowers of her head-dress trembled as she slowly revolved in front of him, the floating, pleated layers of her gown lifting to display golden sandals whose straps circled her pretty ankles and criss-crossed up her lower legs.

“If Proserpina looked like this, who could blame gloomy Dis for snatching her away,” he said huskily, holding out his hand. “I want to keep you here, all to myself.”

Lallie drifted over to him and bent to kiss him quickly but danced away before he could pull down onto his lap.

“Later, sir,” she promised.

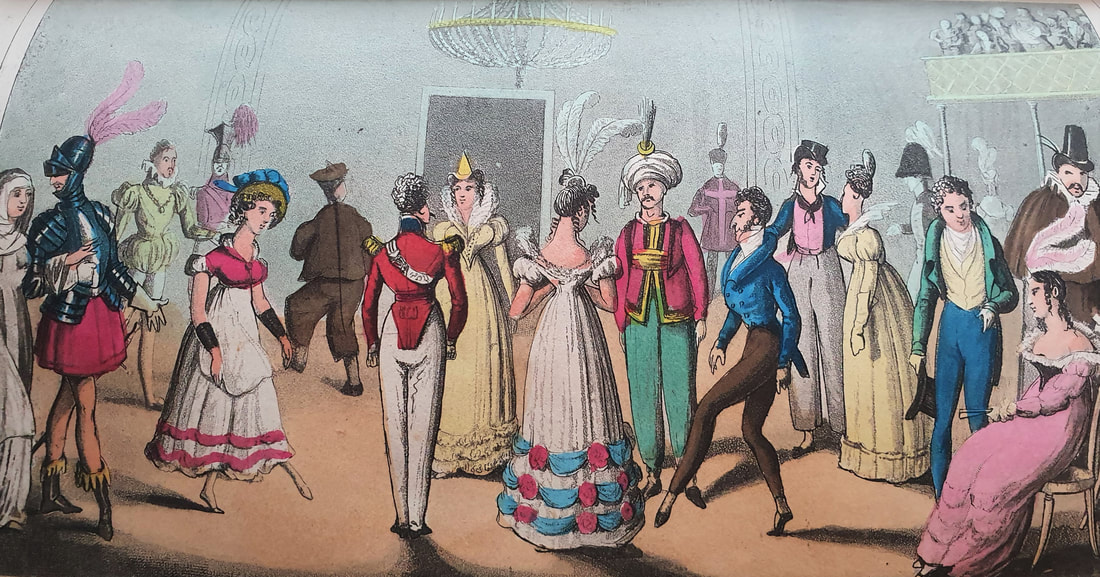

The rich aromas of beeswax candles and burning apple wood, overlain by the scents of countless lotions and distilled, waters pervaded the long ballroom at Malvin Abbey. It was illuminated by four immense crystal chandeliers reflected in numerous gilt-framed pier glasses and over-mantel mirrors that provided infinite glimpses of the swirling throng. A babble of animated conversation vied with the energetic strains of a country reel as Lord and Lady Malvin’s guests joined enthusiastically in the Twelfth Night revels.

“I declare people are so ingenious,” Lady Halworth commented. Clad in the garb of a Contadina—‘I bought the costume in Naples, my dear, so flattering with the waist in its natural place and so easy to wear’—she scrutinized the passing parade. “I’m sure it would never have occurred to me to trick a gentleman out as a knight in armour. It must be very uncomfortable. And look at that mermaid. I daresay she will find her tail an encumbrance if she wishes to dance. Now you, dear Mrs Tamrisk, have combined ingenuity with comfort, and it is most becoming besides, particularly for a lady in your circumstances.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” Lallie murmured. She sat to one side with Lady Halworth and her stepmother, an imposing figure in wimple and veil who looked ‘as if she had modelled herself on an effigy and risen from her tomb,’ according to Hugo’s irreverent comment.

“Yes, one would hardly guess,” Mrs Grey said “and it must be so convenient not to be constantly draping and redraping your shawl.”

“I have Tamrisk to thank for the suggestion of the over-gown. He had the idea from some engravings of antique marbles he purchased while on the grand tour.

“Well, marriage seems to suit you on all fronts,” Mrs Grey said. “You are positively blossoming,” she added with a gentle touch of the gold wreath. “This is so pretty. Where did you find it?”

“Tamrisk presented it to me this evening. I don’t know from where he had it.”

“A paragon among husbands, indeed,” Lady Halworth cried, “and he displays an excellent leg to boot. Now, I see Mrs Ferraunt over there. I must have a word with her.”

“Are you indeed happy, Lallie?” Mrs Grey asked when stepdaughter and stepmother were alone.

“Yes. And I must thank you again for your swift action that night at the inn. And your gift the next morning.”

Mrs Grey looked a little embarrassed. “It was all I could think of. I could not condone forcing you into a distasteful marriage. As for your father’s threat to turn you out! I was horrified. I am glad that everything turned out so well.”

“Aren’t you dancing tonight, Hugo?” Arabella came up to where he stood talking to Clarissa. “The next is a waltz.”

“Lallie finds it too tiring now. But if you are in need of a partner, I should be only too happy oblige.”

“Thank you, but it is too fusty to dance with one’s uncle, no matter how elegant he may be. It would be as bad as dancing with one’s brother. That is for wallflowers.” She smiled coquettishly. “I am promised to Captain Harris.”

“How could I have doubted you! And what of you, Clarissa—did you also take lessons in the waltz last season?”

“She did,” confirmed that lady’s daughter.

“Then, unless of course you would find it too fusty to dance with your brother,” he grinned teasingly at his niece, “perhaps you would do me the honour of standing up with me?”

Clarissa was for once lost for words. She had never waltzed outside the dancing class and Hugo had never before asked her to dance.

“Do, Mama,” Arabella urged her. “Why, we practised the steps only this morning and you were most proficient.”

At that moment Captain Harris arrived to claim his partner and Hugo offered his arm to his sister. With a smile she took it and allowed him to escort her onto the dance floor. At first, they danced silently but then Clarissa gained more confidence.

“It’s different at a ball,” she admitted, “I can see why the young people find it exhilarating, but I must remind Arabella to be particular about the gentlemen to whom she grants a waltz.”

“I don’t think you need worry about her, Clarissa,” Hugo said, “she knows where to draw the line.” He surveyed the gay multitude revolving around them. “My compliments on a most successful evening. What made you think of fancy dress?”

“I wanted something different, but don’t like masquerades – some gentlemen are inclined to take liberties and most of them just throw a domino over their dress clothes. This way everyone must make an effort.”

“There is certainly a great variety of costume. Is that Matthew in the armour? He hasn’t quite got the hang of his sword.”

“It’s only until after the pantomime. It is to be Sherwood Frolics and he is Sir Richard of Verysdale.”

“And Malvin the friar of orders grey, I see. And you? I couldn’t place your character beyond that you are dressed as a peasant woman from the middle-ages.”

“Oh, I’m the Witch of Nottingham Well,” she explained complacently. “I bring Robin back to life after he is killed.”

He laughed as he turned her under their raised arms. “You have made a happy family here, you and Tony.”

“Yes. It’s very much due to him, for I was not used to a home where respect and affection were common currency. I learnt a lot from him.”

“So did I,” Hugo said unexpectedly. “He took me aside at Tamm one time when I had made some obnoxiously cutting remark to you in imitation of my father, and explained to me that one must treat all women with courtesy and respect. Indeed, these characteristics should mark all the dealings of a gentleman, he said. I did apologise to you but I fear it was too late to improve things between us. However, he made me realise that Tamm’s was neither the only, nor perhaps the best example for me to follow.”

The music stopped and they exchanged bow and curtsey. Clarissa sighed. “He tried to get me to see that you had changed and shouldn’t be blamed for yielding to Papa’s early influence, but I was unable to let go. I am so sorry, Hugo.”

“It’s over, Clarrie,” he said. “Please don’t go on punishing yourself; you have suffered enough. We have, both of us, so much more than Tamm ever had and we shouldn’t let him spoil it for us by constantly harking back to the past. Lay it to rest.”

“You’re right. Thank you, Hugo.” She took his arm and they walked off the dance floor. “Lallie mentioned that her connection to the Greys is not as close as it was. I must say I think her father behaved abominably. When I think that she might have had a proper come-out! Those first seasons are so important for girls, you know. They may try their wings and learn a little of the world, make new friendships as well, before settling down.”

“You didn’t have that either, Clarrie, nor did Amabel,” he said sympathetically.

“No. I think I enjoyed bringing out Henrietta, Mattie and now Arabella all the more because of it. I had to muddle through so much, and I was determined they should not have to.”

“I understand, but at least you had Tony to support you.”

“His mother was very kind, too. I had hardly been in society before we went to Bath, for Papa never permitted Mama to go anywhere and Mama-in-law helped me find my feet.”

“Lallie’s other grandmother, Lady Grey, would have brought her out at her own expense, but Grey wouldn’t permit it and never let on that Lallie herself had more than enough money to fund a season if it came to that.”

She laughed shamefacedly. “Do you remember me complaining about her lack of fortune? With that dowry, she might have had her pick of suitors. Not that I think she could have found a better husband than you,” she hastened to reassure him, “and I can see that you are very happy together now, but her father took so many choices from her.”

“She took his deception very hard,” Hugo said, “she felt it as a sort of betrayal.”

“Which it was,” Clarissa stated. “It is the duty of the parent to support the child, not vice versa, unless of course the parent is in genuine need or is old and feeble. Neither can be true of the Greys and I can quite see why Lallie wishes to keep them a little at a distance now. But I know she has no other close family—the Martyn connection is very new to her—and I was wondering if she would like me to come to Tamm to be with her during her confinement.” She spoke hesitantly, as if unsure whether such an offer would be welcome.

“I think she would. It’s very kind of you to offer, but would you not find it difficult to be at the Manor again in such circumstances? I don’t remember it of course but Henrietta has told me of your difficult experiences with Mama.”

“Since then I’ve given birth to four healthy children,” she pointed out. “That might comfort Lallie if she is worried as might only be expected. I’m sure Anthony would come too—you’ll need someone at your side as well. They were the longest hours of his life, he always says, the days his children were born.”

“I should be very grateful,” Hugo said sincerely, “but let me mention it to Lallie.”

“I see I’ll have to learn to waltz,” Anthony Malvin greeted them with a warm smile. “Arabella has been teasing me to do so, but now that I’ve seen you dance it, my lady, I’m determined you shall dance it next with me.”

Lallie caught sight of her husband in the long mirror and turned to inspect him. Following animated discussions that were punctuated by his refusal to wear skirts (as he described any form of robe, gown or tunic) or wigs (which effectively ruled out the preceding two centuries, as he also declined to appear as a round-head), they had settled on Elizabethan doublet and hose which, as she had acerbically pointed out, would be no more revealing than today’s silk knee-breeches or clinging pantaloons.

He cut a very dashing figure in dark burgundy that had been slashed to reveal the gold lining which was pulled through in puffs. The cut of the doublet emphasized his broad shoulders and harrow waist, while a puffed trunkhose served to spare his blushes. His netherhose were also burgundy, but with elaborate gold clocks. A white ruff set off his dark, aquiline features and a short cloak, again lined with gold, hung from his shoulders. Heeled burgundy shoes with gold buckles gave him additional height so that when Lallie stood, she found herself looking up more than usual to meet his eyes.

“You look truly splendid, Hugo. It’s fortunate that we are at your sister’s and not a more public assembly, for you would be besieged by all the females.”

He made an elaborate leg. “My eyes would only be for you, Clio. I had forgotten how delectable you looked in that gown.” He traced the neckline with a caressing finger. “It is even more enticing now. “He bent to kiss her and inhaled deeply. “I remember that perfume.”

“It’s called Les Fleurs du Parnasse’ Do you like it?”

“It’s intoxicating, Clio” he muttered, going on one knee to nibble a line of kisses from her throat to between her breasts.

“Behave, sir, or I’ll never be ready,” she protested, but softened her rebuke by holding him to her for a moment and gently ruffling his hair. He raised his head and captured her in one arm a more satisfying embrace before presenting her with a flat leather box. Lallie opened it to reveal a half-wreath of leaves and flowers cunningly fashioned in beaten gold.

“I asked Henrietta to find something appropriately classical for you to wear tonight,” Hugo explained as she stared at it, spellbound. “I didn’t think I would find the right thing in Exeter.”

“Hugo, this is ravishing. Thank you so much! You spoil me.”

“That is my privilege.”

She twined her arms around his neck to kiss him sweetly. “Thank you,” she said again, “it’s so beautiful and how clever of you to think of it. You must be reconciled with naughty Clio if you purchase her such treasures,” she added with a provocative smile.

“Very reconciled,” he murmured against her mouth. “I think you must wear that gown some evening we’re dining in our apartments.”

Lallie glanced at the clock, “It’s almost time to go down. I must ring for Nancy to help me. She will have to redo my hair without the bandeaux. This will be much prettier.”

“We’ll put on the tunic first, Miss Lallie,” Nancy said, very carefully setting down the wreath. “This is so delicate; only see how each leaf and petal is barely attached so that it seems they might be carried away by the slightest breeze. I’m afraid we’ll damage it if it catches on something as we put it over your head.”

The tunic was a soft pink, made of finely pleated linen that was cleverly cut to skim the swell of Lallie’s abdomen, its asymmetric line cunningly leading the eye away from the evidence of her pregnancy. Instead of sleeves, dropped shoulders, loosely gathered at the seam, covered her upper arms. All the edges were trimmed with entwined green and gold braid, the slight weight of which held the pleats in place.

“You won’t have the matching green in your hair now,” Nancy remarked as she removed the bandeaux and artfully settled the wreath in her mistress’s newly-styled hair

“We still have my grand-mother’s ear-rings.”

Hugo, lounging on the sofa as he watched his wife put the finishing touches to her toilette, caught his breath when she rose from the stool and turned to face him. The sparkle of her green eyes matched that of the peridots suspended from her delicate ear-lobes. The leaves and flowers of her head-dress trembled as she slowly revolved in front of him, the floating, pleated layers of her gown lifting to display golden sandals whose straps circled her pretty ankles and criss-crossed up her lower legs.

“If Proserpina looked like this, who could blame gloomy Dis for snatching her away,” he said huskily, holding out his hand. “I want to keep you here, all to myself.”

Lallie drifted over to him and bent to kiss him quickly but danced away before he could pull down onto his lap.

“Later, sir,” she promised.

The rich aromas of beeswax candles and burning apple wood, overlain by the scents of countless lotions and distilled, waters pervaded the long ballroom at Malvin Abbey. It was illuminated by four immense crystal chandeliers reflected in numerous gilt-framed pier glasses and over-mantel mirrors that provided infinite glimpses of the swirling throng. A babble of animated conversation vied with the energetic strains of a country reel as Lord and Lady Malvin’s guests joined enthusiastically in the Twelfth Night revels.

“I declare people are so ingenious,” Lady Halworth commented. Clad in the garb of a Contadina—‘I bought the costume in Naples, my dear, so flattering with the waist in its natural place and so easy to wear’—she scrutinized the passing parade. “I’m sure it would never have occurred to me to trick a gentleman out as a knight in armour. It must be very uncomfortable. And look at that mermaid. I daresay she will find her tail an encumbrance if she wishes to dance. Now you, dear Mrs Tamrisk, have combined ingenuity with comfort, and it is most becoming besides, particularly for a lady in your circumstances.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” Lallie murmured. She sat to one side with Lady Halworth and her stepmother, an imposing figure in wimple and veil who looked ‘as if she had modelled herself on an effigy and risen from her tomb,’ according to Hugo’s irreverent comment.

“Yes, one would hardly guess,” Mrs Grey said “and it must be so convenient not to be constantly draping and redraping your shawl.”

“I have Tamrisk to thank for the suggestion of the over-gown. He had the idea from some engravings of antique marbles he purchased while on the grand tour.

“Well, marriage seems to suit you on all fronts,” Mrs Grey said. “You are positively blossoming,” she added with a gentle touch of the gold wreath. “This is so pretty. Where did you find it?”

“Tamrisk presented it to me this evening. I don’t know from where he had it.”

“A paragon among husbands, indeed,” Lady Halworth cried, “and he displays an excellent leg to boot. Now, I see Mrs Ferraunt over there. I must have a word with her.”

“Are you indeed happy, Lallie?” Mrs Grey asked when stepdaughter and stepmother were alone.

“Yes. And I must thank you again for your swift action that night at the inn. And your gift the next morning.”