Above:Presenting the Trophies (1815, Rowlandson)

To be hoffähig, that is to have the right to be presented at court, defined your place in society in nineteenth century England. During the long eighteenth century, access to court seems to have been more or less self-regulated. Provided you were well-bred, of good repute and possessed of sufficient fortune to array yourself in court dress, an introduction could be yours. You could only be presented by somebody who had previously been presented and this, together with the instinct of all elites to safeguard their privileges, appears to have been sufficient to see off any encroaching mushrooms.

Belinda, heroine of Maria Edgeworth’s eponymous novel of 1801, has come to stay with the fashionable Lady Delacour for the Season. Her aunt is desirous that she should go to court, and make a splendid figure there and her ladyship informs her, You must go to the drawing-room with me next week, and be presented—as it is the first time, you must be elegantly dressed, and you must not wear the same dress on the birthnight.

By the ‘birthnight’ she means the birthnight court ball held to mark royal birthdays, a glittering if highly regimented occasion where the minuet was danced by one couple at a time, in strict order of precedence. When the minuets were over, two or three country dances were danced but not by the whole company. It is likely that Belinda would not have danced at all, but would have been among the spectators.

As George III’s health declined and his Queen grew older, the custom of holding regular drawing-rooms and balls faded until there was a period of almost two years between June 1810 and April 1812 when no drawing-room was held at all. The fashionable world did not grind to a halt but, as recorded in the Annual Register for the year: 30 April. The Queen held a drawing room at St. James's Palace. It being the first which her Majesty has held since the King's birth day in 1810, and there having been no Court for the ladies during a lapse of nearly two years, great preparations were made by the higher ranks for their appearance on this occasion.”

Going to court required court dress. Belinda’s aunt sends her a draught on her banker for two hundred guineas. 'You will, I trust, repay me when you are established in the world; as I hope and believe, from what I hear from Lady Delacour of the power of your charms, you will soon be, to the entire satisfaction of all your friends. This was a huge sum, the equivalent of almost sixteen thousand pounds today, but, as the novel shows, it was enough to pay only for the ball-gown. Belinda must ‘let her ladyship bespeak for her, fifty guineas' worth of elegance and fashion’ for the drawing-room itself. And all this for gowns that Belinda would probably never wear again because court dress was very different to fashionable dress.

To be hoffähig, that is to have the right to be presented at court, defined your place in society in nineteenth century England. During the long eighteenth century, access to court seems to have been more or less self-regulated. Provided you were well-bred, of good repute and possessed of sufficient fortune to array yourself in court dress, an introduction could be yours. You could only be presented by somebody who had previously been presented and this, together with the instinct of all elites to safeguard their privileges, appears to have been sufficient to see off any encroaching mushrooms.

Belinda, heroine of Maria Edgeworth’s eponymous novel of 1801, has come to stay with the fashionable Lady Delacour for the Season. Her aunt is desirous that she should go to court, and make a splendid figure there and her ladyship informs her, You must go to the drawing-room with me next week, and be presented—as it is the first time, you must be elegantly dressed, and you must not wear the same dress on the birthnight.

By the ‘birthnight’ she means the birthnight court ball held to mark royal birthdays, a glittering if highly regimented occasion where the minuet was danced by one couple at a time, in strict order of precedence. When the minuets were over, two or three country dances were danced but not by the whole company. It is likely that Belinda would not have danced at all, but would have been among the spectators.

As George III’s health declined and his Queen grew older, the custom of holding regular drawing-rooms and balls faded until there was a period of almost two years between June 1810 and April 1812 when no drawing-room was held at all. The fashionable world did not grind to a halt but, as recorded in the Annual Register for the year: 30 April. The Queen held a drawing room at St. James's Palace. It being the first which her Majesty has held since the King's birth day in 1810, and there having been no Court for the ladies during a lapse of nearly two years, great preparations were made by the higher ranks for their appearance on this occasion.”

Going to court required court dress. Belinda’s aunt sends her a draught on her banker for two hundred guineas. 'You will, I trust, repay me when you are established in the world; as I hope and believe, from what I hear from Lady Delacour of the power of your charms, you will soon be, to the entire satisfaction of all your friends. This was a huge sum, the equivalent of almost sixteen thousand pounds today, but, as the novel shows, it was enough to pay only for the ball-gown. Belinda must ‘let her ladyship bespeak for her, fifty guineas' worth of elegance and fashion’ for the drawing-room itself. And all this for gowns that Belinda would probably never wear again because court dress was very different to fashionable dress.

Above, left court gown 1795 and right ball dress and walking dress 1808

Although by the turn of the nineteenth century, the fashion was for light gowns reminiscent of ancient Greece and Rome, the Queen clung to the old elaborate confections of richly trimmed silks and satins supported by the obsolete hoop, described by The Morning Chronicle in January 1795 and deplored by the Persian Ambassador, Abul Hassan in 1810 who recorded the Queen’s ladies as standing from waist to toe in full-blown tents while from waist to shoulders the dresses were closely fitted. As can be seen from Rowlandson's picture at the top of this post, an unfortunate attempt was also made to marry the regency fashion for high-waisted, low-cut gowns with the court requirement for hoops.

It was only in 1820, after the death of Queen Charlotte, that the Prince Regent changed the regulations for court dress, doing away with hoops but retaining the requirement for a lady to wear a train, lace lappets and feathers. Below, Court Dress, July 1824.

In 1810, Abul Hassan noted in his journal that No member of a family touched by scandal is received at court. By the reign of Queen Victoria, the rules regarding eligiblity had ben formalised, perhaps due to the rise of the middle classes.

The etiquette manual The Habits of Good Society (1859) sets out who can be presented at Court. Apart from the wives and daughters of the nobility and gentry, wives and daughters of the clergy, of military and naval officers, of physicians and barristers can be presented. These are the aristocratic professions, but the wives and daughters of general practitioners and of solicitors are not entitled to a presentation. The wives and daughters of merchants, or of men in business (excepting bankers), are not entitled to presentation. Nevertheless, though many ladies of this class were refused presentation early in this reign, it is certain that many have since been presented. No divorcee, nor lady married, after having lived with her husband or with any one else before her marriage, can be received.

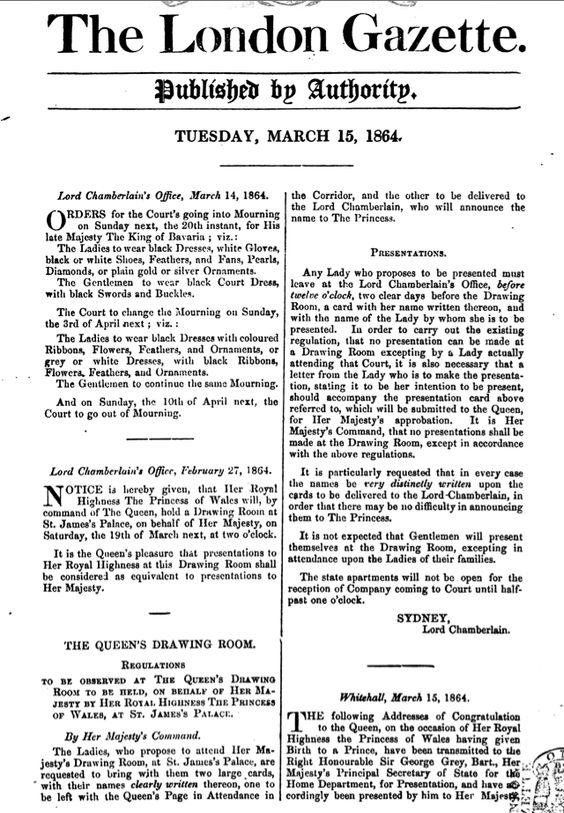

The notices of drawing-rooms also became more elaborate. What had once been a simple announcement in The Gazette, such as this one from 21 December 1816: Notice is hereby given, that Her Majesty’s birth-day which falls on the 18th of January, will be celebrated by a Drawing-Room at The Queen's Palace, on the 6th of February and that the birth-day-of His Royal Highness the Prince Regent will also be celebrated by a Drawing-Room at Her Majesty's Palace, on St George's Day, the 23d of April, by 1864 had become much more dictatorial.

The etiquette manual The Habits of Good Society (1859) sets out who can be presented at Court. Apart from the wives and daughters of the nobility and gentry, wives and daughters of the clergy, of military and naval officers, of physicians and barristers can be presented. These are the aristocratic professions, but the wives and daughters of general practitioners and of solicitors are not entitled to a presentation. The wives and daughters of merchants, or of men in business (excepting bankers), are not entitled to presentation. Nevertheless, though many ladies of this class were refused presentation early in this reign, it is certain that many have since been presented. No divorcee, nor lady married, after having lived with her husband or with any one else before her marriage, can be received.

The notices of drawing-rooms also became more elaborate. What had once been a simple announcement in The Gazette, such as this one from 21 December 1816: Notice is hereby given, that Her Majesty’s birth-day which falls on the 18th of January, will be celebrated by a Drawing-Room at The Queen's Palace, on the 6th of February and that the birth-day-of His Royal Highness the Prince Regent will also be celebrated by a Drawing-Room at Her Majesty's Palace, on St George's Day, the 23d of April, by 1864 had become much more dictatorial.

As the century progressed, the regulations became stiffer and stiffer. According to Etiquette for Ladies (undated) A spinster must appear with two, and a married lady with three, feathers so disposed on her head that they are visible from the front, and with two long lappets of tulle or lace (two yards in length) flowing from the back of the hair. She must wear a low bodice and short sleeves, and a train coming either from the waist or the shoulders, not less than three yards in length. The gloves must be white and never tinted with a colour except in cases of mourning, when black or lavender are allowed. Her train spread out behind her by two lords-in-waiting, she must approach the throne, curtsey as low as possible so as almost to kneel. The Queen kisses her on the forehead if is she is a peeress or peer’s daughter or extends her hand to be kissed if the lady is a commoner.

In the above picture of a presentation to Queen Victoria in 1849, both queen and debutante have removed the glove from their right hand for this ceremony. This contact of skin to skin appears to have been an essential part of a presentation and was, perhaps, a hearkening back to feudal oaths of allegiance. In a letter to his step-daughter Miss Orde of October 1837, the great recorder of the age, Thomas Creevey, wrote: ….the Queen was told that I had not been presented, upon which a scene took place that to me was truly distressing, The poor little thing could not get her glove off…….she blushed and laughed and pulled, till the thing was done, and I kissed her hand.

Etiquette for Ladies continued the description of a presentation as follows: The lady then rises, curtsies to the Prince of Wales and any other members of the Royal family who are present and passes on, keeping her face towards the Queen, and leaving the room in a succession of curtsies.

We must hope she is successful. Manners for Women (1897) records, among other cautionary tales, the dreadful fate of the lady, the heel of whose shoe caught in her skirts and who as a result could not get up after her curtsey. She had to be carried from the Presence Chamber after the manner of the old game of “Honey Pots, causing Queen Victoria to smile broadly. Her Majesty, it appears, could on occasion be amused.