“If I could work my will,” said Scrooge indignantly, “every idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips, should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart.” Charles Dickens A Christmas Carol 1843

My kitchen smells of spice and Christmas from my Christmas puddings, made according to my mother's family recipe. I spent hours as a child 'helping' to rub bread through a sieve to make breadcrumbs or stoning the Valentia raisins. Later I was allowed to chop the glistening pieces of candied orange and citron peel, and enjoy the cook's bonus of the aromatic sugar crystals that first had to be removed. Finally I was shown how to use a very sharp knife to chop the raw beef suet very finely. I felt so grown-up!

Today the work is much less tedious. The breadcrumbs are made quickly in the food processor, we have seedless raisins and the peel comes ready diced. I have substituted butter for the suet which was the last remnant of the medieval plum pottage or plum porridge—a thickened beef broth, spiked with dried fruits and seasoned with spices for a special occasion. Such pottages or porridges were easy to make over a fire and could be adapted and stretched to meet all requirements.

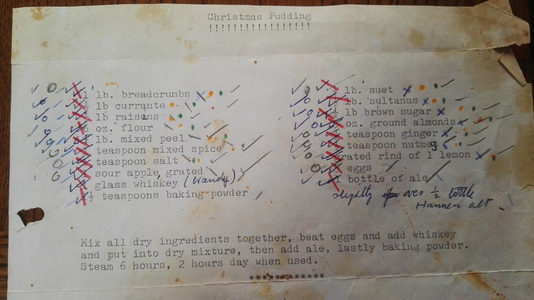

My mother’s old, hand-written recipe was stained and almost illegible due to the different coloured markings ticking off ingredients as they were used. When I married, I took a typed copy with me to Germany where the Christmas pudding became just as much a tradition for my children. Frequently we combined the German and Irish traditions, taking advantage of the six-hour steaming time to bake trays of Christmas cookies and today I made two puddings, one for here in Ireland and one to take to Germany next week. My copy, too, has been replaced over the years as the multiple ticks became too confusing, as you can see from the recipe at the top of this post.

The brief instructions above are for experienced cooks and make two large or four small puddings. If you are interested in trying this recipe and would like more detailed instructions, please let me know, with your e-mail address, at m.me/catherinekullmannauthor .

Was it Charles Dickens who placed the plum pudding at the heart of English Christmas celebrations? In a Christmas Carol it is the first target of Scrooge’s loathing and later the climax of the Cratchit Christmas dinner.

Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastrycook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs. Cratchit entered—flushed, but smiling proudly—with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Oh, a wonderful pudding! Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs. Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs. Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.

Although steamed savoury and sweet puddings were a staple of the English diet, the plum or Christmas pudding is a late eighteenth century variation of a much older dish that goes back to the middle ages. Richard Bradley’s Country Housewife and Lady’s Director of 1736 gives a recipe for Plum-Pottage, or Christmas Pottage which starts by boiling a leg of beef in sufficient quantity of water until it is tender. He then adds two quarts each of red wind and strong beer, cloves, mace, nutmegs, apples, currants, ‘raisins of the sun’ and prunes. He finishes by saying ‘Take out the Beef and the Broth or Pottage will be ready for use’. The beef presumably would be used in another dish or at another, superior table.

The 1753 fifteenth edition of The Compleat Housewife or Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion has a recipe for Plumb Porridge. This starts by putting of a leg of beef to ten gallons of water to make a broth. When the beef is very tender it is removed and the broth then thickened with sliced penny loaves although sago may be used to thicken it instead of bread if you wish. Later currants, raisins and prunes are boiled in this mass until they swell. The porridge is seasoned with mace, cloves, nutmegs, salt, sugar, sack, claret and lemon juice. The recipe finishes with ‘pour them into earthen pans and keep them for use’.

Hannah Glasse repeats this recipe in her 1786 Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy but she also gives a recipe for a boiled plum pudding which uses suet but no broth. Her pudding would have been boiled in a cloth, as Mrs Cratchit’s was.

By 1855, in her revised edition of Modern Cookery for Private Families, Eliza Acton has several recipes for plum and Christmas puddings, including a Vegetable Plum Pudding, based on mashed potatoes and carrots. It still contains suet, so is not vegetarian. Her puddings are cooked in moulds, basins or cloths. The ingredients she gives for The Author’s Christmas Pudding are similar to those in my own family recipe although the proportions vary slightly. She cooks this pudding in a ‘thickly-floured cloth’.

The fame of the plum pudding spread rapidly and by 1866, in the sixth edition of his Anweisung in der feinen Kochkunst or Instruction in the Fine Art of Cookery, J Rottenhöfer, Major-Domo and former personal chef to King Maximilian II of Bavaria describes it as an ‘English national dish’. His recipe is extremely rich, including 280g beef bone marrow, 560g suet and 280g butter as well as the usual dried fruits, spices and breadcrumbs. The pudding is cooked in a napkin that has been coated with butter and strewn with more breadcrumbs.

My mother still used a pudding-cloth of coarse linen to cover the pudding bowl but today I use grease-proof paper and aluminium foil. But I still tie the covers with string the way she taught me, making a handle so that it is easier to lift them out of the water.

My kitchen smells of spice and Christmas from my Christmas puddings, made according to my mother's family recipe. I spent hours as a child 'helping' to rub bread through a sieve to make breadcrumbs or stoning the Valentia raisins. Later I was allowed to chop the glistening pieces of candied orange and citron peel, and enjoy the cook's bonus of the aromatic sugar crystals that first had to be removed. Finally I was shown how to use a very sharp knife to chop the raw beef suet very finely. I felt so grown-up!

Today the work is much less tedious. The breadcrumbs are made quickly in the food processor, we have seedless raisins and the peel comes ready diced. I have substituted butter for the suet which was the last remnant of the medieval plum pottage or plum porridge—a thickened beef broth, spiked with dried fruits and seasoned with spices for a special occasion. Such pottages or porridges were easy to make over a fire and could be adapted and stretched to meet all requirements.

My mother’s old, hand-written recipe was stained and almost illegible due to the different coloured markings ticking off ingredients as they were used. When I married, I took a typed copy with me to Germany where the Christmas pudding became just as much a tradition for my children. Frequently we combined the German and Irish traditions, taking advantage of the six-hour steaming time to bake trays of Christmas cookies and today I made two puddings, one for here in Ireland and one to take to Germany next week. My copy, too, has been replaced over the years as the multiple ticks became too confusing, as you can see from the recipe at the top of this post.

The brief instructions above are for experienced cooks and make two large or four small puddings. If you are interested in trying this recipe and would like more detailed instructions, please let me know, with your e-mail address, at m.me/catherinekullmannauthor .

Was it Charles Dickens who placed the plum pudding at the heart of English Christmas celebrations? In a Christmas Carol it is the first target of Scrooge’s loathing and later the climax of the Cratchit Christmas dinner.

Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastrycook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs. Cratchit entered—flushed, but smiling proudly—with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Oh, a wonderful pudding! Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs. Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs. Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.

Although steamed savoury and sweet puddings were a staple of the English diet, the plum or Christmas pudding is a late eighteenth century variation of a much older dish that goes back to the middle ages. Richard Bradley’s Country Housewife and Lady’s Director of 1736 gives a recipe for Plum-Pottage, or Christmas Pottage which starts by boiling a leg of beef in sufficient quantity of water until it is tender. He then adds two quarts each of red wind and strong beer, cloves, mace, nutmegs, apples, currants, ‘raisins of the sun’ and prunes. He finishes by saying ‘Take out the Beef and the Broth or Pottage will be ready for use’. The beef presumably would be used in another dish or at another, superior table.

The 1753 fifteenth edition of The Compleat Housewife or Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion has a recipe for Plumb Porridge. This starts by putting of a leg of beef to ten gallons of water to make a broth. When the beef is very tender it is removed and the broth then thickened with sliced penny loaves although sago may be used to thicken it instead of bread if you wish. Later currants, raisins and prunes are boiled in this mass until they swell. The porridge is seasoned with mace, cloves, nutmegs, salt, sugar, sack, claret and lemon juice. The recipe finishes with ‘pour them into earthen pans and keep them for use’.

Hannah Glasse repeats this recipe in her 1786 Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy but she also gives a recipe for a boiled plum pudding which uses suet but no broth. Her pudding would have been boiled in a cloth, as Mrs Cratchit’s was.

By 1855, in her revised edition of Modern Cookery for Private Families, Eliza Acton has several recipes for plum and Christmas puddings, including a Vegetable Plum Pudding, based on mashed potatoes and carrots. It still contains suet, so is not vegetarian. Her puddings are cooked in moulds, basins or cloths. The ingredients she gives for The Author’s Christmas Pudding are similar to those in my own family recipe although the proportions vary slightly. She cooks this pudding in a ‘thickly-floured cloth’.

The fame of the plum pudding spread rapidly and by 1866, in the sixth edition of his Anweisung in der feinen Kochkunst or Instruction in the Fine Art of Cookery, J Rottenhöfer, Major-Domo and former personal chef to King Maximilian II of Bavaria describes it as an ‘English national dish’. His recipe is extremely rich, including 280g beef bone marrow, 560g suet and 280g butter as well as the usual dried fruits, spices and breadcrumbs. The pudding is cooked in a napkin that has been coated with butter and strewn with more breadcrumbs.

My mother still used a pudding-cloth of coarse linen to cover the pudding bowl but today I use grease-proof paper and aluminium foil. But I still tie the covers with string the way she taught me, making a handle so that it is easier to lift them out of the water.